Nicky Harman peruses Goodreads for reviews of a classic Chinese novel.

Wednesday, 15 June 2022

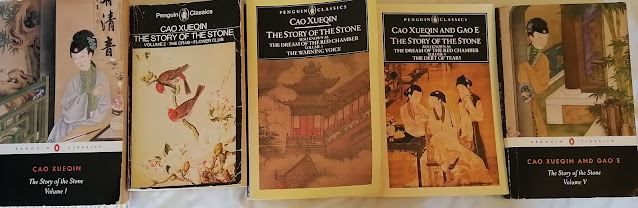

In Praise of Readers' Reviews: The Story of the Stone on Goodreads

Tuesday, 10 May 2022

Translating literature – not such a lonely business after all

Nicky Harman writes: Literary translation, like writing, is traditionally a one-woman or one-man job. At most, two people might work together to translate a book. Large-scale collaborative translation projects are a thing of the past, the far distant past when the Bible and the Buddhist scriptures were translated. But literary translators are resourceful folk and have begun to get together in mutual support groups. Here, I interview Natascha Bruce and Jack Hargreaves, both of whom are active in such groups and agreed to tell me more about them.

Natascha Bruce translates fiction from Chinese. Her work includes Lonely Face by Yeng Pway Ngon, Bloodline by Patigül, Lake Like a Mirror by Ho Sok Fong and, co-translated with Nicky Harman, A Classic Tragedy by Xu Xiaobin. Forthcoming translations include Mystery Train by Can Xue and Owlish by Dorothy Tse, for which she was awarded a 2021 PEN/Heim grant. She recently moved to Amsterdam.

Jack Hargreaves is a translator from East Yorkshire,

now based in Leeds. His literary work has appeared on Asymptote Journal,

Words Without Borders, LitHub, adda and LA Review of

Books China Channel. Published and forthcoming full-length works include Winter

Pasture by Li Juan and Seeing by Chai Jing, both of them

co-translations with Yan Yan, published by Astra House. Jack translated Shen

Dacheng’s short story ‘Novelist in the Attic’ for Comma Press’ The Book of

Shanghai and was ALTA’s 2021 Emerging Translator Mentee for Literature from

Singapore. He volunteers as a member of the Paper Republic management team and

releases a monthly newsletter about Chinese-language literature in translation.

Jack Hargreaves is a translator from East Yorkshire,

now based in Leeds. His literary work has appeared on Asymptote Journal,

Words Without Borders, LitHub, adda and LA Review of

Books China Channel. Published and forthcoming full-length works include Winter

Pasture by Li Juan and Seeing by Chai Jing, both of them

co-translations with Yan Yan, published by Astra House. Jack translated Shen

Dacheng’s short story ‘Novelist in the Attic’ for Comma Press’ The Book of

Shanghai and was ALTA’s 2021 Emerging Translator Mentee for Literature from

Singapore. He volunteers as a member of the Paper Republic management team and

releases a monthly newsletter about Chinese-language literature in translation.Tuesday, 22 February 2022

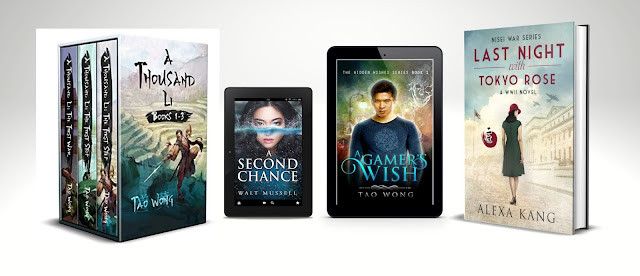

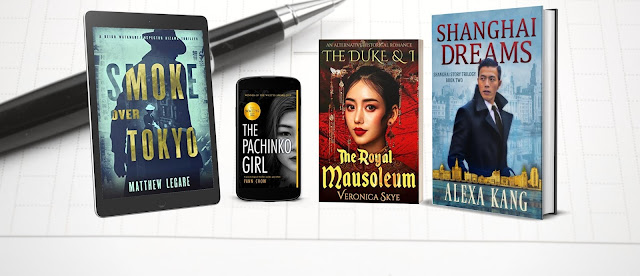

Indie-Spotlight: Selling Books with Asian Main Characters - Part II

Indie Spotlight is a column by WWII historical fiction author Alexa Kang. The column regularly features hot new releases and noteworthy indie-published books, and popular authors who have found success in the new creative world of independent publishing.

Wednesday, 16 February 2022

Indie-Spotlight: Selling Books with Asian Main Characters - Part I

Indie Spotlight is a column by WWII historical fiction author Alexa Kang. The column regularly features hot new releases and noteworthy indie-published books, and popular authors who have found success in the new creative world of independent publishing.

Friday, 15 October 2021

Indie Spotlight: Historical Fiction - When you say ‘authentic’ . . .

Indie Spotlight is a column by WWII historical fiction author Alexa Kang. The column regularly features hot new releases and noteworthy indie-published books, and popular authors who have found success in the new creative world of independent publishing.

As a historical fiction author, I know that readers has a high expectation of historical accuracy in our books. When we write our characters, we strive to make them as authentic as possible to the era when our stories take place. But the more I read and research history, the more I find that people in the past often behave quite differently from what we expect based on our understanding of social norms and customs of their time. Today, I invited author Melissa Addey to join us and discuss what authenticity means when we talk about historical fiction. Melissa is the author of Forbidden City, a Chinese historical fiction series about the experiences of four girls who were drafted to become concubines of the Emperor in 18th century China.

Now, over to Melissa . . .

Friday, 6 August 2021

Serve the People! by Yan Lianke - A Novel of the Chinese Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution has been a taboo subject in China, but confusing and forgotten to Westerners. The political upheavals instigated by Mao Zedong between 1966-1976 were baffling to those who observed and participated. Mao ostensibly sought to create a new, permanent revolutionary China, doing away with old ideas, old customs, and old culture, but his main aim was to purge all political rivals and enshrine himself as a godlike figure, which somewhat continues to this day. It is during this tumultuous era, that the novel Serve the People! by Yan Lianke takes place.

Tuesday, 29 June 2021

Indie Spotlight: A Tale of Two Series - How Author Jeannie Lin Took Took Her Asian Steampunk Series from Traditional Publishing to Independent Publishing Success

Indie Spotlight is a column by WWII historical fiction author Alexa Kang. The column regularly features hot new releases and noteworthy indie-published books, and popular authors who have found success in the new creative world of independent publishing.

The publishing world is rapidly changing with technology. More and more, authors are finding new ways to offer their stories to readers. The limitations of traditional publishing have pushed many authors to leave behind the old model and try out all the new opportunities to expand their readership and get their books into the hands of the readers.

Our column today features Jeannie Lin, a USA Today Bestselling author of Chinese historical romance and historical fantasy. She is the author of the Gunpowder Chronicles, a Chinese historical steampunk series set in the Qing Dynasty that was originally published by Penguin. Here, Jeannie tells us the fascinating tale of how she took back the rights of the Gunpowder Chronicles, which was languishing under Penguin, and re-released it independently to make it a success.

Also, the final book of the Gunpowder Chronicles series, The Rebellion Engines, was just released on June 28. Be sure to check out this exciting series with a very different historical spin.

Now, over to Jeannie . . .

Sunday, 6 June 2021

The Girl Who Played Go by Shan Sa

The Girl Who Played Go is a historical novel by Chinese author Shan Sa, originally published in French, translated into English. With that many international filters, it is surprising how well it evokes the Chinese mindset, but also, the Japanese side as well.

Wednesday, 21 April 2021

The Mountain Whisperer – Another novel to add to the Jia Pingwa canon, reviewed by Nicky Harman

Jia Pingwa, ‘China’s master story-teller’ as the launch event for Mountain Whisperer dubbed him, remains relatively unknown to the English-language reader although a number of his novels have been translated. For anyone wanting to make his acquaintance, there is Turbulence, translated by Howard Goldblatt (1991); Happy Dreams, (Nicky Harman, 2014); Ruined Capital (Howard Goldblatt, 2016); Backflow River, (Nicky Harman, 2016, a free-to-read novella); The Lantern Bearer, (Carlos Rojas, 2017); Broken Wings (Nicky Harman, 2019); Shaanxi Opera, forthcoming; and now, Mountain Whisperer translated by Christopher Payne, and published, in a beautiful edition, by Sinoist Books, 2021.

Even judging by the small collection which has been translated (a tiny part of his oeuvre), what is striking is the range of Jia’s writing: panoramic epics, rural and urban, with a cast of hundreds or the ‘small stories’ (Jia’s words) with a mere half-a-dozen; from ebullient characters we can imagine meeting anywhere, to the fey and the frankly oddball ones we are only likely to meet in the pages of his novels.

Mountain Whisperer is one of Jia’s epics, hefty, though conveniently divided into four books set in different historical periods. Its unifying thread is the funeral singer, the eponymous mountain whisperer, one of Jia’s fey characters. As he lies dying in a cave high in the mountains of Shaanxi, he tells the stories of a soldier, a peasant, a revolutionary and a politician, and the parts they played in the struggles that forged the People’s Republic of China from its turbulent birth to its absurd reversal.

And yet, the real protagonist of Mountain Whisperer could be said to be the land itself. Jia describes how it has shaped the lives and culture of local communities and embellishes his own writing with excerpts from an ancient compilation of mythic geography and fabulous beasts, Pathways Through the Mountains and Seas.

There is insufficient space here to give a proper synopsis of the whole novel. I will just say that, of the four stories, my personal favourite is the fourth, about a man called Xi Sheng of very short stature. This section brings us bang up to date. So much so, in fact, that we have a scarily prescient description of a pandemic – scary because this novel was written in 2013, Jia tells us. Of course, another coronavirus hit China and other countries in 2003, ten years before this novel was written. But the description of how the epidemic struck the villages is eerily familiar, today. ‘From the national capital it extended its tendrils throughout the country, leaving no place untouched. The first symptoms were akin to catching a cold: a headache, blocked nose, fever, joint pain and incessant coughing. Once the infection made its way into the lungs, death would follow shortly. The people in Qinling took to cursing the southerners, then Beijingers, all asking the same question: how the hell had it spread to Qinling?’

It would be remiss of me to finish this review without devoting some space to Jia Pingwa’s Afterword. Every novel he writes has one, and they are remarkable: extended essays which describe how he dreamed up the novel, what challenges he faced as he wrote it, the real-life elements that he has fictionalized, and what this particular novel means to him personally. For this last reason alone, I thoroughly recommend reading it, perhaps even before you begin the book. A 500-page novel about a place where you have never been and are never likely to go to, can seem daunting. But the Afterword of Mountain Whisperer takes us, the readers, by the hand, sits us down with Jia Pingwa, and allows us to listen as he talks from the heart. Here is a small excerpt:

Three years ago, I returned to Dihua [Jia’s birthplace], on the eve of the lunar New Year. I visited my ancestors’ graves and lit a lantern to remember them. This is an important custom in the countryside, and if lanterns aren’t lit for some graves, it means there is no one left in the family to light them. I remember kneeling down in front of them, lighting a candle, and then the darkness that hung around me grew even denser. It seemed as though the only light in the entire world was the one emanating from the small candle I held. But... my grandfather’s visage, my grandmother’s too, as well as the forms of my father and mother, they were all so clear! ….

From Dihua, I returned to Xi’an and for a long time I remained silent, uncommunicative, often shut up in my study doing very little, except for smoking. And there, in those clouds of tobacco that blanketed my study and swirled about my head, I recalled the past decades, time seemed to flutter by, unstable, fleeting, surging in great waves of reminiscences... the changes wrought on society over the past hundred years, the wars, the chaos, the droughts and famines, revolution, political movements upon movements, then the reforms and to a time of relative plenty, of safety, of people living as people. Then my thoughts drifted to my grandfather and what he had done with his life. I wondered how he had lived, and how his son had come into this world, my father and his life, and the lives of the many townspeople from the place we called home.

……

In [the Qinling mountains] I saw so many ancient trees, the cassias with large, yellowish leaves that draped down their trunks like finely woven baskets, as well as gingko trees with trunks so wide it would take four men to wrap their arms around them. I also saw the people who lived in the mountains, often busily rebuilding homes, and there within their compounds planting many saplings. There are times when life can surprise and amaze you, and there are other times when it is cruel and vile. The mountain whisperer is like a spectre wafting across Qinling, decades upon decades, winding his way through the affairs of this world without obvious reason, without clear intent or form, solitarily observing the lives as lived but never delving in too deeply, never becoming too involved. Then, finally, death visits him. Everyone dies, and so too does every age. We see the world rise to great heights and then we see it fall. The mountain whisperer sang songs of mourning, and those same songs welcomed him into the netherworld.

Tuesday, 13 April 2021

Indie Spotlight: Cozy Mystery Author Anne R. Tan

Indie Spotlight is a column by WWII historical fiction author Alexa Kang. The column regularly features hot new releases and noteworthy books, and popular authors who have found success in the new creative world of self-publishing. In this column, Alexa chats with Anne R. Tan, USA Today best-selling author of the Raina Sun Mystery series and the Lucy Fong Mystery series. Her humorous cozy mysteries feature Chinese-American amateur sleuths dealing with love, family, and life while solving murders.

What is a cozy mystery, and why do you write them?

A cozy mystery is typically a mystery with no gore, sex, or foul language. The bad guy is always caught at the end, and life returns to normal. Since I was a teen, my favorite reading genre is cozy mystery. However, the amateur sleuths are rarely a person of color.

The lack of diversity didn’t bother me until the birth of my daughter in 2011. I can find books with Chinese characters, but if the books are set in the U.S., the stories are usually about the immigrant experience. And if the books are set in Asia, the stories are “exotic and foreign.” While feeding my infant in the wee hours of the morning, I had a Jerry Maguire moment. I will write books that are more relatable to my American-born Chinese (ABC) daughter.

What is the inspiration for your books?

My Raina Sun Mystery series features a third-generation ABC from a large Chinese family. Raina Sun is your average grad student. She has the same concerns as everyone else—mounting bills, a boatload of Ramen…and murder. With her zany grandma as her sidekick, Raina stumbles on one dead body after another. Her ethnicity and culture shape her viewpoint and the course of the investigations.

There are many aspects of the Chinese culture and beliefs my daughter will never experience because we live so far from a major Chinese hub like the San Francisco Bay Area. I hope to document these cultural aspects in my books.

Why do you indie publish your books?

I indie published my first book in 2014 after my son's birth (my children changed the trajectory of my life). While my books follow the cozy mystery genre expectations, a traditional publisher would never pick them up.

I have a Chinese-American sleuth, a diverse cast, and Chinese culture. And Raina Sun travels, so she doesn’t always stay in her small town or neighborhood. These books are the American experience of Chinese families that have lived in America for multiple generations. Traditional publishers like to publish the Chinese immigration experience of my grandparents, and while that is important, they are not as relevant to my children.

Interestingly enough, a big traditional publisher offered me a three-book deal a few years ago when diversity became desirable. However, their version of diversity is still too restrictive, so I declined the offer. I love the creative freedom of indie publishing.

What is your writing process like?

I am a civil engineer (yes, I love math). With a full-time job and young children, I write in the cracks of life. Hence, I write more than half my books on my phone. While my children are doing their after-school activities, I am tapping away on the sidelines. Sometimes I scribble thoughts into notebooks.

The creative life, while rewarding, is all consuming at times. You give up your hobbies and sometimes even essential activities to finish the book. Even though I set my own schedule by indie publishing, I still have deadlines. If I do not turn in my manuscript on time, it has a rippling effect on my editors and release dates. And I also get emails and messages from disappointed readers. Once the book is done, I take several months off to recharge and do everyday stuff like cleaning up the house and buying clothes for my children.

Is there anything else you’d like readers of this blog to know about you and/or your books?

If you're interested in a humorous cozy mystery with a dash of family drama and Chinese culture, the eBook for Raining Men and Corpses (Raina Sun Mystery #1) is free at all major retailers. A wacky Chinese grandmother loves to supply my main character with “weapons of mass destruction” in each book. Thank you for hosting me.

To learn more about Anne and her work, you can visit her website at http://annertan.com

Wednesday, 4 December 2019

Prizes and parties...

In my more pessimistic moments, I feel Chinese novels translated into English are a hard sell and I’m not sure when or if they will ever become part of the literary ‘mainstream’ in the West. My friend the poet and novelist Han Dong concurs: he reckons that Chinese fiction in foreign languages will never sell like western fiction translated into Chinese. You may or may not agree with his reasoning: Chinese readers are exposed from childhood to life in the west, through classic and new translations, books, films and TV series. But that familiarity doesn’t work the other way around. So Chinese literature doesn’t capture readers’ imagination.

I thought about this argument and wondered: so then do we only read fiction that describes worlds we are familiar with? Well no… not exactly. Just look at the winner of the 2019 Man Booker International prize, Jokha Alharti. Her novel, ‘Celestial Bodies’, is about Omani tribal society, hardly a place most of us have lived in or are familiar with. But it is a beautiful, captivating read.

Wednesday, 23 October 2019

My Travels in Ding Yi. Nicky Harman looks at the latest translated novel from Shi Tiesheng

One of the most interesting novels to come out in translation this year is My Travels in Ding Yi (ACA Publishing, 2019) by Shi Tiesheng (1951-2010).

Shi's writing ranges widely, from disability, to reflections on philosophy and religion, to magical surrealism, to an entertaining vignette on football and a meditation on his local park and his mother. However, he first became famous for writing his personal experiences of being disabled. One of his most famous short stories is The Temple of Earth and I (translated by Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping), in which he talks movingly about the frustrations he faced, and how he and his mother struggled to cope. Back in the 1980s, discrimination against the disabled was embedded into the language and society alike. Sarah Dauncey in her paper, Writing Disability into Modern Chinese Fiction, Chinese Literature Today, 6:1 (2017) says that '...canfei 残废 (invalids) was still the accepted equivalent to the English terms disability and disabled with all its retained connotations of uselessness and rubbish as reflected in particular by the fei 废 character.'

Wednesday, 25 September 2019

The History of a Place in a Single Object, with Multiple Variations

Wednesday, 26 June 2019

Nicky Harman interviews Jeremy Tiang, Singaporean writer, translator and playwright

Nicky: When you were growing up, what were the first Chinese-language stories you came across, and what drew you to them?

Jeremy: Growing up in a former British colony can be a destabilizing experience. Singapore's official languages are English, Chinese (meaning Mandarin), Malay and Tamil, and there were always several languages swirling around me ― some of which I felt I was being encouraged to know (the English in the Enid Blyton books my parents bought us, the Mandarin they sent me to a neighbour to learn) as well as others I had less access to (the Cantonese they sometimes used with each other, the Tamil my dad occasionally spoke on the phone). I encountered Chinese stories in all kinds of ways, on TV and in my school textbooks, but often freighted with cultural baggage: there was a weight of obligation on us, as English-educated people, to hang on to our Chinese heritage. It wasn't until I got some distance from Singapore, by moving to the UK for university, that I was able to enjoy Chinese-language literature on its own terms. While I came to appreciate the grounding I had received in Singapore, particularly in secondary school, I don't think I read a Chinese novel for pleasure till I was in my twenties. Once I was able to do that, I quickly developed a taste for it. And being a writer of English and a lover of Chinese fiction, it was a logical progression to literary translation ― the best way I could think of to get right inside these books.

Wednesday, 27 March 2019

A New Kid on the Block for Literary Nonprofits

Wednesday, 27 February 2019

My chance to talk for an hour about Chinese literature -- with an excellent interviewer

I had slightly mixed feelings when Georgia de Chamberet and I began our podcast for Bookblast. On the one hand, it was a great opportunity to talk both about the literary translation website I work on, Paper Republic, and the range of novels that feature on our 2018 roll call of Chinese translations into English. On the other hand, Georgia’s questions required some serious thought and I felt I was in danger of making wild generalizations (perhaps inevitable when you’re talking about a country and a literature as big as China). What follows is an excerpt from our Q+A. I hope you’ll find it thought-provoking enough to listen to the full podcast.

Friday, 1 February 2019

Paper Republic 2018 roll call of translations

Balanced between the Western new year and the Chinese New Year of the Pig, Paper Republic has just launched its 2018 roll call of published English translations from Chinese. With 33 novels, six poetry collections and three young adult or children’s titles, it’s a unique resource you won’t find anywhere else on the web.

The roll call includes titles from established authors such as:

Wednesday, 30 January 2019

Broken Wings, Jia Pingwa's novel about a trafficked woman, in translation

Wednesday, 12 December 2018

Friday, 16 November 2018

Obituary for Louis Cha, by John Minford

Between 1997 and 2002, John Minford, now Emeritus Professor of Chinese at the Australian National University, brought out a three-volume translation of Cha's The Deer and the Cauldron, with Oxford University Press Hong Kong (OUP HK). Now OUP UK has published it in the UK. John here provides an obituary for Louis Cha.