Editor’s note: Here in Singapore, public conversation has in recent weeks revolved around the fate of the island’s forests – sanctuaries of diversity within a crowded city-state. This month’s guest post by Leonard Yip, excerpted from his recently-completed MPhil dissertation, explores the trajectories of place- and nature-writing in Singapore poetry, and draws our attention to how the ‘twin languages of grief and hope’ cast a familiar terrain in new light.

***

In his poem ‘Clementi’ (2019), Singaporean poet Alvin Pang describes the titular neighbourhood as

a riverrimmed reefknot of […] woods, mosques, stadium, pool, defunct purposebuilt buffet edifice, bioswales. Park connectors haunted by the Great White God of the waterway (photoevidence on request) (saidtobe komodo dragon wor, sureornot), a maw bigger than the monitors that monitor the stream and get picked on by otter gangs. Greyheads and whitebellied lurkers, raptorial and sometimes rapturous, hauling telelens on extended tripods. Wings bluelasering the wavers while the abacusclacker of massrail passings encount indifferent intervals.

Pang’s work does not pretend towards neat, organised overview of place. A riotous composition of poetic sensitivity to rhythm and prosaic attention to detail, ‘Clementi’ formally embodies the area it describes: a chaotic compress of countless lives, seething together . The terrain of poem and place defy categorisation – religious, recreational and natural structures of ‘woods, mosques, stadium’ build together undifferentiated, vowels and consonants accelerating together with restless rhythm.

Set loose from containment, things collide and intermingle freely. The vernacular of Clementi’s residents mixes with hushed myth: a lizard water-god, ‘saidtobe komodo dragon wor’, the suffix a Singlish invocation of emphasis, and the incredulous response ‘sureornot’. Genres as well as languages smash into each other, the great lizard’s high mystery fraying into gangland turf war as smooth-coated otters vie with monitors for territory. Language turns loose; ‘Greyheads and whitebellied lurkers’ describes both middle-aged, enraptured birdwatchers and the watched raptors themselves, melding human observer and animal subject. Words come together in onomatopoetic portmanteaus, birthing a new soundscape for this strange place, where urban and natural generate new forms: the ‘abacusclacker’ of a passing train, consonants clattering against the skimming, sheeting ‘bluelasering’ of wings slicing the water’s edge. This place is an interface of lives morphing into one another, a land animated by accommodations and adaptations.

Pang’s lands are my lands. I know this ‘riverrimmed reefknot’ for myself, these taut words suggesting the landscape’s own denseness. I grew up in it, tracing my way through park connectors and bioswales to canal edges, where linen-scented laundry outflow washes into loach shoals glittering in the water grasses. A landscape such as this can be frustrating to read. Theories and poetics of either urban architecture or sublime, untouched wildness fall flat, insufficient for making sense of a space as mixed between the two as this. They are lands at each other’s fringes, neither fully wild nor urban – edgelands.

This term was first coined by the British writer and activist Marion Shoard in 2000, to describe the land ‘betwixt urban and rural’, which was ‘a kind of landscape quite different from either’. It describes many of Singapore’s terrains which do not fit cleanly into urban or natural categories, where human infrastructure marries itself to the wildness of nature, springing new ecologies into life. These terrains, however, also exceed the term’s original, Anglocentric definitions. Where Shoard understood the edgelands as a transitional zone between city and countryside, Singapore’s small landmass and extensive development mean that the countryside is city. The edgelands detonate out of the compression between our dense neighbourhoods and teeming biodiversity – both products and victims of our land-altering and devastating. Great metal machines up-end the forest, laying down concrete drains where macaques sneak into backyards and morning glories bloom over fences. These go in time, too, as bulldozers churn the earth again to prepare new superstructures of metal and glass. The edgelands are terrains of the Anthropocene, disappearing as fast as they form.

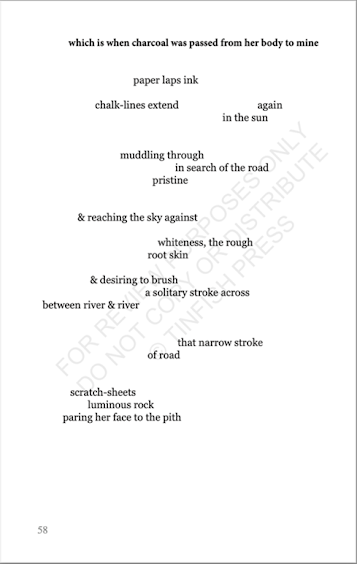

The violence which creates and destroys the edgelands extends not just across the earth, but into it as well. Redeveloping land erases and builds over past traces of life, razing ecologies, histories and memories. Because of this, the cultural activity which articulates our relationship to the edgelands often does so through a language of grief and memory. Chitra Ramesh’s poem ‘Merlion’ (2019) evokes the history of Singapore’s modernisation, where swamps were drained and zinc-roofed villages razed to make way for public housing:

if you dig the marshy wet soil

you might find the roofs of my kampong house

roosters might mumble under those roofs

fish may be still gasping through their gills

among the flowers in my garden

[…]

Under the expressways

our thatched houses lie buried.

Ramesh’s imagination figures national and personal history as fantastic revenants haunting the city’s underworld: disquiet roosters in the soil, and fish clinging on to amphibious half-life. Childhood memories persist uncomfortably in the earth like stubborn residue, the ‘gasping’ of fish suggesting a suffocating struggle for survival. Wistful, yet resolute, Ramesh’s landscape is an edgeland of chronology as well as ecology, containing and conjuring memories back to ward off their forgetting. This language of grief and ghosts is critical for surviving in the Anthropocene, because it refuses the geographic amnesia of what ecologists call ‘shifting baseline syndrome’ – when our landscapes become so altered that we forget what was there before. Ramesh’s edgeland poetry is held hostage by its summoned spectres, and this holds us in turn accountable – to remember the stratified layers of meaning and home-making beneath our feet.

The edgelands, however, can also be read with a language of hope as much as grief. The same sensitivity which allows us to mourn what is lost enables us to imagine what might still be possible, between the human and more-than-human presences that compose these places. Observing smooth-coated otters returning to Singapore’s city-centre reservoirs and waterways, Cyril Wong’s ‘Otter City’ (2019) both wrestles with and affirms the tentative relationships forming within the edgelands’ compress:

how long have we been watching

with love and envy -

leaving us lovers and doubtful

urbanites to lumber back to the m.r.t.,

noting sporadically trees

we cannot name – tembusu

or angsana, we wished we knew –

and that sudden, darting shrew

skirting us between office buildings.

those otters still

whirling through our minds –

our date complete; not just

with each other

but with a whole republic

of life thrumming beneath our feet.

Wong’s verse initially charts estrangement and frustration. Ocular connection between otter and observer produces only a reminder of how alien each one seems to the other. The watchers appear to be drawn apart from the wild rather than reconciled to it, so detached they cannot even name the trees.

Yet something wonderful happens in the poem: the otters stay ‘whirling through [their] minds’, extracting the transfixed watchers from the self-obsession of their date, and extending the occasion’s opportunity for intimacy to ‘a whole republic of life’. The phrase unites our manmade polity with the creatures slinking back through this city, becoming as much a part of it as the watchers. Wong’s poem finds its way ultimately to a kind of entrancement – human and animal test the waters, learning to shape the colliding spheres of their existence. The path blazed by Wong’s work illuminates how the twin languages of grief and hope might help us to read these complicated, threatened terrains: tracing a route from what we are not, into the possibility of what we could be; one entire ‘republic of life’, living, nourishing, and benefiting each other within the edgelands’ interface.

***

Leonard Yip is a writer of landscape, people, nature and faith, and the places where these intersect. He recently graduated with an MPhil in Modern and Contemporary Literature from the University of Cambridge, where he wrote his dissertation on multimedia representations of the edgelands of Singapore. His writing has been featured in Moxy Magazine, Elsewhere: A Journal of Place, and Nature Watch, the quarterly publication of the Nature Society (Singapore). He lives in Singapore, where he is currently furthering his work on the edgelands and other terrains of the Anthropocene. More of his work can be found at leonardywy.wordpress.com.

Note: Alvin Pang's and Chitra Ramesh's poems can be found in 'Contour: A Lyric Cartography of Singapore', ed. Leonard Ng, Azhar Ibrahim, Chow Teck Seng, Kanagalatha Krishnasamy, Tan Chee Lay (Singapore: Poetry Festival Singapore, 2019). Cyril Wong's poem is published in 'The Nature of Poetry', ed. Edwin Thumboo and Eric Tinsay Valles (Singapore: National Parks Board, 2019).

Cover photo by Theophilus Kwek.

%20(1).jpg)