Editor's note: We're delighted to feature a review of Tse Hao Guang's latest collection by another gifted Singapore poet, Mok Zining. Tse was previously featured on the blog here, and has also written for us here. Thank you both for gracing our poetry column!

“The International Left-Hand Calligraphy Association is a real place,” read the epigraph. “Please come in and touch everything.” Turning the page, I stepped in, finding a miscellany of things hanging suspended in the shifting light: a dragonfly wing, the words of Simone Weil, a landfill of folded plastic triangles, a Chinese idiom unstrung and reworked, rust disappearing at the oxidation of starfruit juice.

Such was my first impression of The International Left-Hand Calligraphy Association (Tinfish Press, 2023), a collection rendered with lightness and light. This second full-length collection by Tse Hao Guang contains poems composed in a visual form that evokes fluidity and looseness; rather than verses of lines, each poem looks more like a constellation of words and phrases bounded by the page. Seen through the lens of the collection’s title, the visual form of these poems evokes the brushstroke movement in certain styles of Chinese calligraphy, in particular the cursive and semi-cursive scripts.

At the same time, these visual forms also call to mind such modernist poetic interventions as erasure and collage, as well as the Fluxus experimentation with concrete poetry, of which John Cage’s ‘Lecture on Nothing’ is a precursor. Notably, Tse does not seem interested in the practice and idea of Chinese calligraphy as a “traditional” art form or pinnacle of Chinese classicism. This decentering of a uniformly defined Chinese cultural inheritance is evidenced by poems like and ‘is Chinatown your burden? limitless like the universe?’ and ‘two minute Buddha Jumps Over the Wall’. Rather, Calligraphy seems more interested in the possibilities that can be opened by rendering these found objects and languages in the intermediate spaces Tse occupies. A poem that demonstrates this generative stance is ‘this moment’, a free translation of the Chinese poet An Qi’s 《此刻》(cike), excerpted here:

I was struck by how naturally the syntax of this poem, though very much inflected by the Mandarin, fit in Calligraphy. This free translation also brings a visual dimension that isn’t found in the original, lineated text. In their delightful mirroring of the sunlight “threading/ through” the rooftop, the words “17th floor/ 16th floor/ 15th floor” themselves seem to direct the eye to fall, as light, upon the architecture of the poem. Like ‘this moment’, Tse’s two other “free translations” of An Qi’s poems, ‘so & so’s terrace’ and ‘hands part when day is not yet light’, are certainly highlights of the book.

Calligraphy signals quite a departure from Tse’s first full-length collection, Deeds of Light (Math Paper Press, 2015), which featured the poet at ease in a range of formal poems. Revisiting Deeds for this review, however, I was struck by the pertinence of its epigraph, taken from Goethe’s Theory of Colours: “Colours are the deeds of light, its deeds and sufferings.” What carries over from Deeds is Tse’s visual sensibility – his careful attention to the quality, color, and movement of light falling on an object or a landscape.

In Calligraphy, this sensibility is heightened and made performative. Images mutate and transfigure effortlessly. Reading ‘this morning I woke up w/ a quick laugh like the sun’, for example, I found myself thinking it read almost like a script or storyboard for a video poem:

In the space of a page, Tse weaves together a poem that morphs effortlessly from the image of nails (intimate, mundane) to the sun and moon (celestial, symbolic, grand) and back to dust (infinitesimal). Facilitating this cinematic effect is the loose visual form, which enables an image to shape-shift by unsettling the fulfilment of the poetic line.

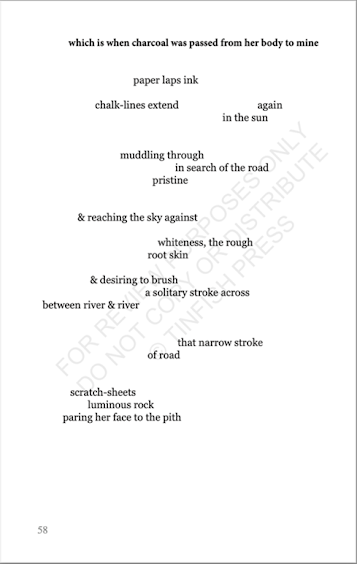

The visual effect is more impressionistic in other poems, with their abilities to craft a sensation of visual form. A good example is ‘which is when charcoal was passed from her body to mine’:

While reading this poem, I felt as if images that rhymed visually – “chalk-lines,” “a solitary stroke,” the land “between river and river,” “that narrow stroke/ of road,” and the very action of paring – were rising to the fore of my mind. Unlike ‘quick laugh’, ‘charcoal’ uses few transitions and connecting words to create visual development. Tse instead pares each fragment down to its visual bone before composing them in a stream-of-consciousness logic. Indeed, the experience of reading Calligraphy feels like we are following the speaker’s mind as it moves about the world, picking up on and stringing together a range of found languages and images – including AlphaGo, Stephen Chow films, the work of artists like Ivan David Ng. The book’s title is in this sense less an overarching representation of the project than one of the many found poems gathered for this collection, as Calligraphy takes its name from an organization in Katong Shopping Centre that supports left-handers who wish to learn the art of Chinese calligraphy.

Something could probably be said here about how the collection exhibits a sort of “lefthandedness” in its occupying of the space between media, between Sinophone and Anglophone poetic traditions, and between languages. However, this was also where I, a maximalist, found myself wondering if there was an opportunity for the collection to experiment more with visual form in this intermedia space. What might a visual composition that plays with the type of typographic research undertaken in the concrete poetry movement and Chinese calligraphic scripts (which include not just cursive and semi-cursive scripts, but also the oracle bone and seal scripts) look like, for example? What are some possibilities between typographic poetry and the work of artists like Wu Guanzhong or Lim Tze Peng? What if the collection took its own epigraph at a more literal level and referenced not just the name of the organization, but also its locale in Katong? Still, The International Left-Hand Calligraphy Association contains many moments of brilliance, beauty and whimsy, and I would be interested to see how its experiments with the visual might shape poetic practices in Singlit.

***