Editor's note: We're delighted to feature a review of Tse Hao Guang's latest collection by another gifted Singapore poet, Mok Zining. Tse was previously featured on the blog here, and has also written for us here. Thank you both for gracing our poetry column!

“The International Left-Hand Calligraphy Association

is a real place,” read the epigraph. “Please come in and touch everything.” Turning

the page, I stepped in, finding a miscellany of things hanging suspended in the

shifting light: a dragonfly wing, the words of Simone Weil, a landfill of

folded plastic triangles, a Chinese idiom unstrung and reworked, rust

disappearing at the oxidation of starfruit juice.

Such was my first impression of The International Left-Hand Calligraphy Association (Tinfish Press, 2023), a collection rendered

with lightness and light. This second full-length collection by Tse Hao Guang contains

poems composed in a visual form that evokes fluidity and looseness; rather than

verses of lines, each poem looks more like a constellation of words and phrases

bounded by the page. Seen through the lens of the collection’s title, the

visual form of these poems evokes the brushstroke movement in certain styles of

Chinese calligraphy, in particular the cursive and semi-cursive scripts.

At the same time, these visual forms also call to mind

such modernist poetic interventions as erasure and collage, as well as the

Fluxus experimentation with concrete poetry, of which John Cage’s ‘Lecture on

Nothing’ is a precursor. Notably, Tse does not seem interested in the practice

and idea of Chinese calligraphy as a “traditional” art form or pinnacle of

Chinese classicism. This decentering of a uniformly defined Chinese cultural

inheritance is evidenced by poems like and ‘is Chinatown your burden? limitless

like the universe?’ and ‘two minute Buddha Jumps Over the Wall’. Rather, Calligraphy

seems more interested in the possibilities that can be opened by rendering

these found objects and languages in the intermediate spaces Tse occupies. A

poem that demonstrates this generative stance is ‘this moment’, a free

translation of the Chinese poet An Qi’s 《此刻》(cike),

excerpted here:

I was struck by how naturally the syntax of this poem,

though very much inflected by the Mandarin, fit in Calligraphy. This free

translation also brings a visual dimension that isn’t found in the original,

lineated text. In their delightful mirroring of the sunlight “threading/

through” the rooftop, the words “17th floor/ 16th floor/

15th floor” themselves seem to direct the eye to fall, as light,

upon the architecture of the poem. Like ‘this moment’, Tse’s two other “free

translations” of An Qi’s poems, ‘so & so’s terrace’ and ‘hands part when

day is not yet light’, are certainly highlights of the book.

Calligraphy signals quite a

departure from Tse’s first full-length collection, Deeds of Light (Math

Paper Press, 2015), which featured the poet at ease in a range of formal poems.

Revisiting Deeds for this review, however, I was struck by the

pertinence of its epigraph, taken from Goethe’s Theory of Colours:

“Colours are the deeds of light, its deeds and sufferings.” What carries over

from Deeds is Tse’s visual sensibility – his careful attention to the

quality, color, and movement of light falling on an object or a landscape.

In Calligraphy, this sensibility is heightened

and made performative. Images mutate and transfigure effortlessly. Reading ‘this

morning I woke up w/ a quick laugh like the sun’, for example, I found myself

thinking it read almost like a script or storyboard for a video poem:

In the space of a page, Tse weaves together a poem that

morphs effortlessly from the image of nails (intimate, mundane) to the sun and

moon (celestial, symbolic, grand) and back to dust (infinitesimal).

Facilitating this cinematic effect is the loose visual form, which enables an

image to shape-shift by unsettling the fulfilment of the poetic line.

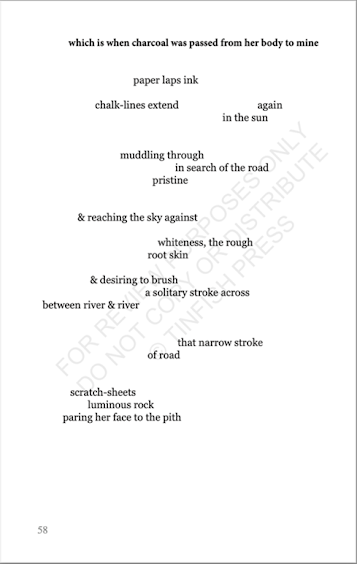

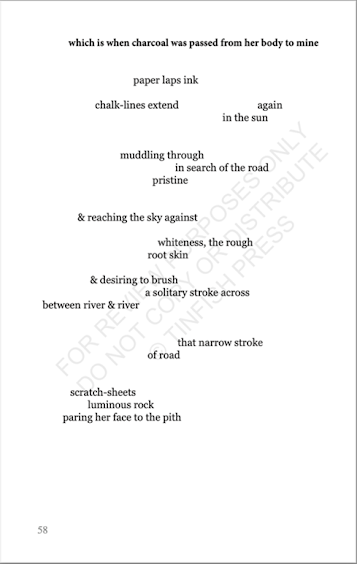

The

visual effect is more impressionistic in other poems, with their abilities to

craft a sensation of visual form. A good example is ‘which is when charcoal was

passed from her body to mine’:

While reading this poem, I felt as if images that

rhymed visually – “chalk-lines,” “a solitary stroke,” the land “between river

and river,” “that narrow stroke/ of road,” and the very action of paring – were

rising to the fore of my mind. Unlike ‘quick laugh’, ‘charcoal’ uses few

transitions and connecting words to create visual development. Tse instead

pares each fragment down to its visual bone before composing them in a

stream-of-consciousness logic. Indeed, the experience of reading Calligraphy

feels like we are following the speaker’s mind as it moves about the world,

picking up on and stringing together a range of found languages and images –

including AlphaGo, Stephen Chow films, the work of artists like Ivan David Ng. The

book’s title is in this sense less an overarching representation of the project

than one of the many found poems gathered for this collection, as Calligraphy

takes its name from an organization in Katong Shopping Centre that supports

left-handers who wish to learn the art of Chinese calligraphy.

Something could probably be said here about how the

collection exhibits a sort of “lefthandedness” in its occupying of the space

between media, between Sinophone and Anglophone poetic traditions, and between

languages. However, this was also where I, a maximalist, found myself wondering

if there was an opportunity for the collection to experiment more with visual

form in this intermedia space. What might a visual composition that plays with

the type of typographic research undertaken in the concrete poetry movement and

Chinese calligraphic scripts (which include not just cursive and semi-cursive

scripts, but also the oracle bone and seal scripts) look like, for example? What

are some possibilities between typographic poetry and the work of artists like

Wu Guanzhong or Lim Tze Peng? What if the collection took its own epigraph at a

more literal level and referenced not just the name of the organization, but

also its locale in Katong? Still, The International Left-Hand Calligraphy

Association contains many moments of brilliance, beauty and whimsy, and I

would be interested to see how its experiments with the visual might shape poetic

practices in Singlit.

***

Mok Zining is obsessed with random things: orchids, arabesques, sand. Her first book, The Orchid Folios (Ethos Books 2020), was shortlisted for the 2022 Singapore Literature Prize in English Poetry. Currently, she is at work on an essay collection, The Earthmovers.