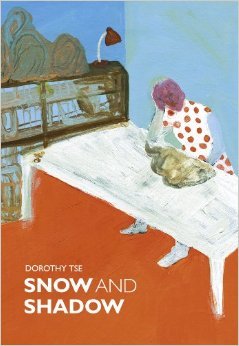

Nicky Harman is a much-acclaimed

translator of Chinese into English. She

focusses on fiction, poetry and occasionally literary non-fiction, by authors

such as Chen Xiwo, Han Dong, Hong Ying, Xinran, Yan Geling and Zhang Ling. Her

translation of Dorothy

Tse's Snow and Shadow is on the longlist for

the Best Translated Book Award 2015.

I’ve just come back from my first visit to the Chengdu Bookworm Festival where, amongst other things, I ran an evening workshop on literary translation. I’ve run such workshops before, but usually over a couple of days rather than a couple of hours. The first challenge was to dream up some"outcomes" for the publicity blurb. What possible outcomes could we expect from a bare two hours working on a text no longer than 850 Chinese characters (around 500 English words in translation) with a group with no or little prior experience of literary translation? Bookworm and I settled on something along the lines of: “…participants will be led through the process of how to achieve accurate, nuanced translations of literary fiction from Chinese to English. A rare chance to explore the subtleties of how language conveys cultural context.Participants should register and do some work in advance.”

The wording must have done the trick: 35 eager participants turned up and, yes, almost all had done their homework in advance!

I confess my heart sank a little when I was told that only about four native-English-speakers had signed up. The general rule for literary translation is that you always translate into your native

language, the language in which you, as a writer, have the best developed and most subtle powers of expression. In this case, I needn’t have worried: there were more than four people with English as their mother tongue (English MTs), and some of the Chinese MTs had an extremely good command of English.

My author was Yan Ge, a Chengdu literary star who has appeared frequently at the Bookworm festival. She made her name as a young author writing what, in the West, would be called young adult fiction (though I know she prefers not to be pigeon-holed in this way). But for this event, I chose an excerpt from her very grown-up novel, The Chilli Bean Paste Clan (in Chinese 《我们家》), whose anti-hero is a philandering businessman who attempts to drink and screw himself into an early grave in the bars and brothels of a fictional small town near Chengdu. I’m not sure what the participants were expecting but I think the amount of bad language in even this short excerpt caused some initial surprise. It certainly livened up the atmosphere. Who could possibly keep a straight face when solemnly discussing whether the light fitting was dangling, sagging or drooping, impotently or otherwise? And, yes, the sexual innuendo was absolutely appropriate in the context. There was much laughter, and that’s always a good sign that things are going well.

As far as the practicalities of the workshop went, we got the participants to sit and work at tables in groups of half a dozen. This combats the tendency to dose off when something difficult is being

discussed in a large group (I’m not exempting myself from that sin) and, in any case, small group work is much less intimidating. We started with an initial pep talk from me, along the lines of:"…Don’t be afraid to brain-storm…let your linguistic imagination run riot…and remember, there is no single correct translation, but a large number of fruitful possibilities….” And then they were let loose on the text for about an hour. Yan Ge and I circulated between the tables, making encouraging noises and answering questions. Each table had a “scribe” with a laptop, who wrote down each sentence as the group agreed on it.For the last half-hour, each group got to read out their renditions, thankfully with the help of a good roving mike – yes, practicalities really are important.

Group translations of this type are never going to be smooth and polished, but that’s not the point. Instead, I was bowled over by the imaginative translations and the enthusiasm with which they were

produced. I spent a happy hour this morning noting down some feedback for the group participants… happy, because I’m still chuckling at some of the stuff they came up with. Here are just a few examples:

One paragraph talks about the prostitute who is our hero’s first sexual experience. Her name is 红幺妹, literally something like “red little sister”. To translate or not to translate? Years ago, I started my translation career completely opposed to translating names, on the grounds it made them sound more exotic in the English than in the original Chinese, but I’ve moderated my views. Especially in a novel intended for the general reader, why not give a colourful character a colourful name? One group chose to call the prostitute “Tiny Ruby”, which certainly made me smile.

Then there was the last line of the excerpt, when our hero drops the bombshell that his mistress is pregnant. “给你们说,”他宣布,“老子又把婆娘的肚皮搞大了。” There were some triumphs in the English translations, such as: "Gentlemen," he announced. "Guess who went and got another lady pregnant." And: “I'll tell you what,” he announced. “Daddy’s knocked another girl up.” Incidentally, “Daddy” is a nice way of dealing with “老子” ([your] father), the name by which our hero, only half-mockingly, refers to himself when he feels he is not being accorded the respect he is due.

And finally…that 婆娘, a disparaging way of referring to a woman, or women, that is used throughout the novel. Yan Ge and I had many conversations about this. The problem is that it’s pejorative, but not as pejorative as bitch in English. The hero routinely refers to women as婆娘,including his middle-aged wife. The groups produced girl, lady (perhaps not pejorative enough), and chick. Chick fits here but not in the rest of the book (because his wife is too old to be called a chick,though it’s fine for his young lover). One day I should get a workshop to brainstorm misogynistic names used by men for women…[stupid] cow, that woman etcetera etcetera…and vice versa.

Between American and British English, there is fertile ground for translation inventiveness. In the meantime, I still wake up in the middle of the night, trying to think of the ideal solution! If authors

are never satisfied with their work, then neither are translators.

Did we achieve the desired outcome? Perhaps it was always going to be something of a tall order: “how to achieve accurate, nuanced translations of literary fiction.” I think it would be truer to say

that participants got a taste of the challenges of translation, including that most knotty of problems, how to achieve the all-important balancing act between respecting what the author has written (and how she’s written it) and producing something that will achieve the intended effect on the English-language reader. I hope that some of our participants, at least, were inspired and might go on to try some translation on their own in the future.

My thanks are due to the Bookworm Festival for taking a punt on this new (to them) format of workshop – and to the help and support of the organisers, especially Catherine and Joanne, who made it run so smoothly.