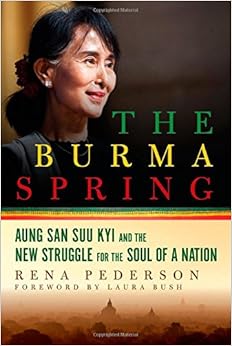

The Burma

Spring,

by award-winning journalist and former US

State Department speechwriter Rena Pederson, is a biography

of Aung San Suu Kyi. It offers a

portrait of the woman herself, and also portraits of Burma, and of the Burmese

people. (Burma was renamed Myanmar by the military government, but since this was not

democratically elected, Western policy has often been to refer to the country

as Burma. Rena adopts this policy too.)

Showing posts with label Q & A. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Q & A. Show all posts

Tuesday, 31 March 2015

Tuesday, 24 March 2015

Q & A with Cheryl Robson

I asked Cheryl about

her life and about Aurora Metro, and its big

ambitions.

Labels:

Q & A

Wednesday, 12 November 2014

Lion City Lit: Q & A with R Ramachandran

Following on from the success of Singapore Writers Festival, we realised here at Asian Books Blog that we ought to give greater coverage to what's going on in our own backyard. The result is Lion City Lit, our new Singapore slot. Here, Rosie Milne talks to R Ramachandran, executive director, National Book Development Council of Singapore.

Singapore aims to position

itself as a centre for publishing of Asian content - it wants any writer with

content relating to Asia to think of it as the place to publish. It helps that the country has four official languages: English; Chinese;

Malay; Tamil. The vibrant local publishing scene is unusual in that it has houses specialising in each language. As part of its strategy to win pre-eminence in the region, the National Book

Development Council makes a number of awards through the Singapore Literature

Prize, which has categories in each language sector. The 2014 awards were announced last week. I asked Mr. Ramachandran about the tiny City-State’s big ambitions.

How does the Singapore Literature Prize contribute to raising Singapore's profile as a centre of publishing?

Books can be eligible even if they are not published in Singapore, and the

award system is geared to grow both to include books published throughout Asia,

and also to include a larger number of categories and languages than at

present.

Other than administering the

Singapore Literature Prize, what else is the National Book Development Council

doing to promote publishing in Singapore?

In order

to serve as an effective centre of Asian content, we need to develop our

translation resources so that Asian content in other languages can be

translated into English and published in Singapore. Such translated works could

be more easily marketed in the region and beyond than could books in Asian

languages. We are planning to set up a translation centre to facilitate translation

of literary works into different languages. We have also upgraded our established

training body, the Academy of Literary Arts and Publishing, to develop the skills

of those in the local publishing industry.

Doesn’t the City-State’s small

size and small books market limit its ambitions?

No. We

publish for the world. For instance, each year we organise the Asian Festival

of Children’s Content. This brings together content creators and

producers, publishers, teachers, librarians and anyone interested in quality

Asian content for children. The Festival carries the slogan: Asian Content for the World’s Children. But it’s not just children’s publishing, we

want all our local publishers to publish beyond the region to the world

market, as do publishing houses in the US and the UK.

Have you learned from other small countries, which have had a big literary impact? I'm thinking of Ireland.

We have

not only studied Ireland, but also Israel and New Zealand, countries whose

writers and creative people have made an impact on the rest of the world. The

great advantage these countries have over us is a longer tradition of

literature and a culture of publishing. Singapore is a migrant state, and a

relatively new one, and even though our fathers and forefathers came from

nations with rich cultural traditions – China, India, the Malay world - they

migrated for materially better lives. Singapore’s early years were essentially

spent on day-to-day matters and economic concerns were predominant. Since

independence, after 50 years of post-colonial development, cultural interests

have come to the fore. The growth of libraries, museums, art galleries,

performing art centres, and a host of other services have emphasised the

importance of the arts.

Okay, but are Singapore’s publishing

ambitions driven by commerce, or culture?

Singapore

has always been a commercial city and it will continue to be. But great commercial

cities also emerge as centres of culture. Take London and New York in the

present day, and Alexandria and Venice in earlier times. All are great examples

of cities that are or were centres of the arts made possible by their

commercial wealth. While commerce and banking are the foundations of wealth in

Singapore, it has also realised the important part culture plays in people’s

lives and is committed to nurture Singapore as a global city of the arts.

The government has spent billions developing arts infrastructure, for example

setting up the National Arts Council,

the Media Development Authority, the School of the Arts, LaSalle College of the

Arts, and the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, to train, nurture and support

creative talent.

An international publishing

industry needs an international rights marketplace. Are there any plans for

Singapore to develop a books fair and rights market?

Yes, the

Singapore Book Publishers Association is planning to set up such a fair. The

Book Council hopes to be involved in this effort. Meanwhile, the Book Council

has developed a marketplace for children’s contents called Media Mart as part

of the Asian Festival of Children’s Content. We want Media Mart to become

known as the foremost regional rights fair for children’s content.

Labels:

Lion City lit,

Q & A

Wednesday, 9 July 2014

Q & A: Susan Barker / The Incarnations

Susan Barker’s newly-published novel The Incarnations is the book club pick

for July – see the previous post for a plot summary. Susan was born in the UK, to a

Chinese-Malaysian mother and an English father.

As an adult, she moved to Beijing, where she spent several years

researching ancient and modern China, before returning to the UK. She then

moved back to China, to Shenzhen, and she currently lives in Beijing. Her

earlier novels are Sayonara Bar, about

a graduate student from England who takes a job at a hostess lounge in Osaka, and

The Orientalist and the Ghost, which

explores Malaysia’s 1950s Communist insurrection, and its continuing impact

down to the 1990s. All Susan’s novels

are published by Doubleday. The

Incarnations is available in hardback, priced in local currencies.

Here Susan answers some questions I put to her by

e-mail.

What

drove your return to China, after you moved back to the UK? Why are you

currently based in Beijing?

I moved to Shenzhen in June 2012, to stay with my

boyfriend who was working for the Chinese tech company Huawei. We lived in the

industrial suburbs in the north, where Foxconn and Huawei are. I lived in

Shenzhen for about 20 months. My boyfriend quit Huawei this past March, and we

moved to Beijing. Shenzhen was really interesting. It is a city of migrants,

everyone comes from another province, so I met people from all over China.

While

you were working on The Incarnations

did you ever feel that writing in English distanced you from your characters

and subject matter? If so, how and why?

I’ve been studying Mandarin since mid-2007 when I

first moved to Beijing, but am far from fluent. I don’t feel writing the novel

in English distanced me from my characters or subject matter though. Language

is a medium of expression, and that which is expressed, i.e. the characters’

thoughts, emotions and behaviour, does not vary much with the language that is

used. There are surface cultural and sociological differences between China and

the UK that I took into account when writing my characters, but I don’t see

these differences as being predicated upon language. Linguistically, my

characterisation and dialogue is not very different from many Chinese novels

that have been translated into English. Of course, I avoided using overly Western

slang and colloquialisms.

Is

a Chinese translation likely? If so, would you want any input into the translation?

I would love for The Incarnations to be translated into Chinese. In the past

when my novels have been translated into another language I had minimal or no

involvement. I think it is best to let the translator have free reign.

What

drew you to write about reincarnation?

When I started researching and writing The Incarnations in 2007, I knew I

wanted to write a novel set in contemporary Beijing, as I was interested in

urban China and the speed of development and social change. I was also

fascinated by Chinese history, which is rich with narratives of revolution and

war and the rise and fall of emperors, and I knew I wanted to write stories

from different historical eras and weave them into the modern-day narrative.

At the risk of demystifying the novel and writing

process, the idea of reincarnation in the novel was initially a narrative

device; a way of structuring the novel and bringing together all of my separate

research interests in China past and present. But over the years, as I wrote

draft after draft of the novel, the reincarnation aspect gained substance and

became the essence of the book.

The idea of reincarnation and recurring souls also

links to one of the major themes of the novel, which is the cyclical nature of

history. The taxi driver Wang Jun keeps repeating the same destructive mistakes

in each of his past lives, due to innate flaws in his nature (wrath,

self-interest, possessiveness, jealousy) that recur life after life. History is

repetitious too, with the same large-scale destructive power struggles playing

out generation after generation, arising from the same innate human flaws.

Do

you believe in reincarnation? Do you believe you have had earlier

incarnations? If so would you be willing to give details? … Or do you

think asking you about your own beliefs about reincarnation is like asking a

crime novelist if they’d ever commit murder?

I am not sure whether or not I believe in

reincarnation. Perhaps I do in my more irrational moments, but it’s a vast leap

of faith to believe you’ve had past lives. My sister once met a medium when we

were teenagers, who said that she (my sister) and I have been linked together

for several past lives, but obviously I am sceptical.

Was

it daunting writing about 1000 years of Chinese history? Did you ever feel

overwhelmed by history?

The

Incarnations has five historical stories

(ostensibly the five past incarnations of the main character, the taxi driver

Wang Jun). The first story is set during the Tang Dynasty, the second story is

set during the invasion of Genghis Khan, the third is about imperial concubines

during the Ming dynasty, the fourth is set during the Opium War, and the last

story is about Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution.

When I started writing the novel in 2007, I knew I

wanted to include historical stories, but I wasn’t sure which eras I would

write about. So I read books that gave a broad overview of Chinese history from

the Qin dynasty to Chairman Mao, and when I came across a historical period or

figure who was especially interesting to me, I would deepen my research in that

area (i.e., find every book I could on the subject). As I read and made notes,

ideas for plot and characters would surface from my research, and I would

proceed from there.

I was slightly daunted by the amount of research I

had to do for each historical story, but at the same time, I like being

challenged and immersed in a long project. I had no idea that The Incarnations would take six

years to write though – I thought it would be three years at the most. I

definitely would’ve been overwhelmed if had I known back in 2007 how long it

would take to write this book.

Were

you worried about the historical accuracy of your novel, or not?

As well as Chinese history the stories are

influenced by Chinese folklore and superstitions, and as a result are quite

surreal and fantastical in places. As a fiction writer I don’t feel constrained

by historical fact in the same way a historian would be. I was able to take

inspiration from historical incidents like the Mongol invasions or the Opium

War and build on them creatively. The stories do deviate from historical fact,

but this did not concern me.

Why

should readers read The Incarnations?

I hope that the sections in contemporary Beijing

offer a snapshot of urban China, and that the historical sections offer a

glimpse of each era (though, as stated above, The Incarnations is nothing like a history book). I really

believe that the reader should be entertained, and wrote the plot(s) with that

in mind, and was inventive with my use of language. Characterisation is really

important to me too, and I worked hard to make sure my characters are

multi-faceted, and psychologically and morally complex.

More Information

www.susanbarker.co.uk

Labels:

Q & A

Monday, 23 June 2014

Q & A: Wendy Wong on eBooks In Asia

|

| Tusitala's logo is a kitsune, a fox with 9 tails, which features in Japanese, Korean and Chinese folklore |

Wendy Wong is Studio Manager

/ Creative Director of Tusitala. The

name is Samoan for storyteller, or a teller of tales – fitting, since Tusitala is a digital publisher of indie authors. The

company is based in Singapore, and is a huge fan of Asian content and Asian

writers.

I

spoke to Wendy about eBooks in Asia generally.

Are eBooks as popular in Asia as in the west?

Not yet, since there are issues around availability and accessibility.

Can you expand on that?

One of

the biggest barriers to eReading in Singapore and in Asia generally is that the

larger providers of eBooks – Amazon and Apple iBooks – don’t allow for potential

readers in Asia to buy eBooks directly. To make an eBook purchase on your

Kindle, for example, you’d need an American address and credit card. If you’re

especially dedicated, you’d find a backdoor entry, and the locally available service

Kindle Concierge can purchase eBooks on your behalf, so you can bypass all the

off-putting red tape, but most local eBook enthusiasts end up with libraries of

pirated eBooks.

Google

Play Books has recently entered Asia, and at Tusitala we hope that Amazon and

Apple will follow Google’s example by expanding into the largely untapped Asian

market, thus making eReading more commonplace.

Aren’t there any local eBook

retailers?

In

Singapore, local eBook stores come and go. Amongst those that survived are

Booktique and M1 Learning Center, yet little is done to publicize their

services to the general public. (Note, in Hong Kong, eBooks are readily

available through Paddyfield.)

Given the problems of

availability, how aware of eBooks are readers in Asia?

I think

readers may be aware of eBooks, but local authors are often unaware of how easy

it is to publish digitally and to access worldwide markets. At Tusitala, as digital

publishers, we do our part to celebrate Asian content and to get Asian authors

to try ePublishing. It isn’t always easy, but we believe that it is a

necessary process that will end with a more vibrant and locally relevant eBooks

scene, certainly in Singapore, and then more generally in the rest of Asia.

Do you think libraries have a

role in helping raise awareness of eBooks?

Yes. In

Singapore, National Arts Council data shows that eRetrievals at libraries

across the island have recently seen a spike; in response the National Library

has expanded and diversified its collection of eBooks to include more languages

and titles. The National Library Board has also been quite vocal lately about

their eBook borrowing campaign, and we hope that this encourages people to

consider eReading as the convenient and hassle-free experience that it is.

What about the language issue? Are eBooks available in languages other than

in English?

Sure. In Singapore, local content in Chinese, Malay

and Tamil is abundant. But while there is no dearth of quality Asian-language

content, people here primarily read in English. I expect this aspect of eBook

publishing in Asia varies market by market.

I see the

main advantage of eBooks as giving me access to content that wouldn’t otherwise

be available to me in Asia. What do you

see as the advantages?

Reading habits have adapted to the fast-paced

lifestyles of developed Asia – increasingly, people consume news or articles on

their phones. By comparison, reading books seems to be a choice that needs to

be made (do I lug a novel through my commute?), not an option that is readily

available on readers’ gadgets (let me scroll to my e-reader app), and eBooks

can help level the field between surfing for information, and reading for

pleasure.

I

sometimes find eBooks frustrating, for example, in non-fiction titles, flipping

to illustrations, or trying to follow footnotes. Do you think the format has any disadvantages?

This is not a disadvantage of eBooks per se, but in

Asia I think the ecology of reading is such that academic reading is

encouraged in young people, rendering reading a habit that doesn’t generally

integrate with everyday life - there is a tendency to associate reading with passing exams, rather than

reading for pleasure.

What are your thoughts on the future of eBooks in

Asia?

The eBook scene has potential for huge growth, and eBooks

are surely set to become more popular, but, as I mentioned already, it’s a matter

of availability. At Tusitala we hope Google

Play Books’ entry into Asia marks the beginning of burgeoning accessibility to eBooks

in the region. We hope this encourages local writers in Asia to start telling

their stories to an ever-expanding audience.

All in all, we are optimistic about the future of eBooks

in Asia. When accessibility and awareness align, we hope that eBooks can change

the perceptions towards reading for pleasure, and thus foster a more inclusive

and pervasive reading culture that everyone can be a part

of.

Do

you have a message for potential authors?

If you

are an author of a book with Asian content and you are looking for a digital

publisher to get your existing printed edition made available as an eBook, or to publish

a new title, we would be very glad to connect with you!

Labels:

Q & A

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)