|

| Felix Cheong, courtesy of author |

About the Author:

Felix Cheong has written 23 books across different genres, including poetry, short stories, children’s picture books and flash fiction. His works have been widely anthologised and nominated for the prestigious Frank O’Connor Award and the Singapore Literature Prize. He has also collaborated across disciplines with musicians and artists.

Conferred the Young Artist Award in 2000 by the National Arts Council, Felix has been invited to writers festivals all over the world, including Edinburgh, Austin and Sydney. He holds a masters in creative writing and is currently a university adjunct lecturer. SPRAWL is his first graphic novel.

|

| Arif Rafhan, courtesy of Arif Rafhan |

About the Illustrator:

Arif Rafhan is a comic artist based in Malaysia. His work can be seen in publications both in Malaysia and Singapore, Gila-Gila magazine (Malaysia), anthologies, and webcomics. He also works with Lat (Kampung Boy) as his inker and colourist. He has also collaborated with Felix Cheong on a second graphic novel, Eve and the Lost Ghost Family.

|

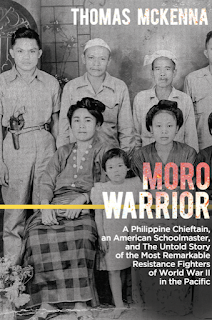

| Book cover, courtesy of Marshall Cavendish |

About the Book:

A hardboiled detective. His knuckleheaded partner. And a bar girl with a mysterious past.

Their lives intersect in the most unlikely of places – a murder scene, where a minister who supposedly killed himself 20 years ago, is found dead again.

In the tradition of noir comics like Sin City, Sprawl is gritty and laced with dark humour. Innovative and surprising in its blend of poetry and art, SPRAWL is the first in a new graphic novel series by Felix Cheong and Arif Rafhan.

_______________________________

EC: Welcome to Asian Books Blog, Felix and Arif. Congratulations on SPRAWL (Marshall Cavendish, 2021), a hardboiled detective graphic novel involving a murder and a police conspiracy. How did the book come about and what is your collaboration process?

FC: This book has been more than 10 years in the making, would you believe it? It began as a verse novel. Back when I was pursuing my masters [at the University of Queensland], almost poet and his pet dog Down Under was writing a verse novel. I thought I’d give it a go, especially after watching The Monkey’s Mask, a verse novel by Dorothy Porter adapted into a film.

The trigger for the story was “Sprawl”, a song about the chaos of the city by Arcade Fire. The lyrics had its hooks on me for the longest time. I imagined a noir-ish, Sin City-like Singapore. Corruption at the highest level of society, filtering down to the cops.

But after 14-15 poems, the story was stuck in a rut. As with most things mouldy, I just left it alone. In 2020, I picked it up again after publishing In the Year of the Virus (Marshall Cavendish, 2020). That poetry comic book gave me the confidence to write differently. Poetry not as standalone lines on the page, but as narrative handmaiden to art. That was when I approached Arif.

AR: Our collaboration was 100% virtual. We had a chat on the phone and once we got aligned creatively, we continued our discussion through text messages. Basically, I would provide visuals and modify them accordingly, based on Felix's feedback. But Felix has been gracious and letting me go wild with my imagination. So, I am very thankful.

FC: Your wild imagination is just right for the book!